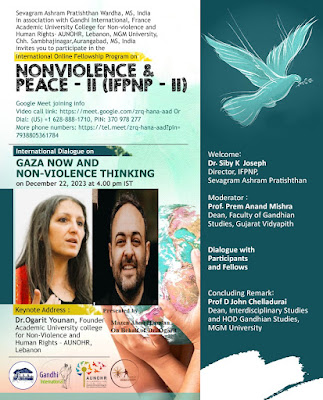

International Dialogue on GAZA NOW and NONVIOLENCE THINKING

On December 22, 2023 at 4 pm IST

About Dr. Ogarit YOUNAN

Email: o.younan@aunohr.edu.lb; younan.ogarit@gmail.com

She devoted her life to humane commitment and nonviolent struggle.

• A pioneer Arab woman for Non-Violence.

• The author of the Non-Violence Education in Lebanon.

• A sociologist, researcher, writer, activist, and a reference in modern training.

• Founder of AUNOHR University with the late Walid Slaiby the Arab nonviolent thinker; unique higher education institution worldwide: Academic University college for Non-Violence and Human Rights; www.aunohr.edu.lb

In 1983, in the wake of the Lebanese war (1975-1990), Ogarit Younan met Walid Slaiby, (the late

Walid Slaiby which passed away in May 2023), and together embarked on a joint journey of life and

struggle for 40 years, under exceptional circumstances. Their commitment and ideas influenced millions in Lebanon and the Arab world, of youth, activists, teachers, intellectuals, media, workers, marginalized communities, political actors, women, etc. and spread to various local and regional

committees, institutions, and programs. Thus, they came to be known as pioneers of the renewal of civil society in Lebanon: The ‘fathers’ of the new civil society.

She is known to be the first to have integrated the culture of nonviolence and the conflict resolution in the official curricula in Lebanon.

She has more than 20 titles of research and publication, in: Education, political socialization, the history schoolbooks, the religious schoolbooks, the personal status and civil marriage, the death penalty, the compulsory military service, the women’ empowerment, the culture and philosophy of nonviolence...

In addition to academic texts, pioneer bulletins for human rights, manuals and training guides, articles, lectures, short stories, and poems.

Ogarit Younan sees herself in a permanent ‘philosophical thinking’, in a beautiful friendship with education and nonviolent action, to love and work, day by day...

• In 2019, AUNOHR and its founders received the Chirac Foundation Prize for “Conflict Prevention”.

• In December 2022, Younan and Slaiby received together The Gandhi International Award (Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation).

• In June 2023, Younan was awarded the Honoring Doctorate of Humane Letters by LAU university in Beirut (The Lebanese American University).

• In 2005, Slaiby and Younan were awarded together by the Human Rights Prize of the French Republic for their pioneer struggle against the death penalty since 1997.

Dr, Ogarit Younan wrote reflective text written in the first week of the war of October 2023 Gaza, Now ! The 8 points stressed by her are following :

1. Our humanity, our humanism, above all

2. An immediate ceasefire. Urgent common goals.

3. Let’s not forget that the root cause is occupation

4. The war on and by civilians

5. The political result is the question

6. Two violent camps, based on religious ideology, currently lead the ring of combat

7. We cannot equate the violence of the oppressor to the violence of the oppressed. And we do not justify any violence whatsoever.

8. We are not doomed to unilateral violence. The responsibility of the non-violent.

To see the text of the article

CPNN

Culture of Peace News Networkhttps://cpnn-world.org/new/?p=

It was published also in the November 15, 2023 issue of Newsletter of Gandhi International . She has been continuously reflecting on it

About Mr. Mazen Abou Hamdan

Mazen Abou Hamdan is an expert in good governance, peace-building, and civic engagement. He is a Chevening Scholar and he has recently completed a Master’s degree in “Conflict, Governance, and International Development” in the UK. He has also completed the courses of another Master’s degree in “Nonviolence and Human Rights” at the Academic University College of Nonviolence and Human Rights (AUNOHR). Mazen is a key activist in Lebanese nonviolent movements, and he is a trainer and an author of several training manuals on Human Rights Education, mediation, Nonviolent Communication, Nonviolent Direct Action, good governance, and advocacy.